Kinship

When studying the Kurds, it is important for anthropologist to try to understand Kurdish kinship because unlike in the United States of America, most of the social interactions among Kurdish people are rooted in kin relationships rather than common interests. For example, when two Kurds meet for the first time, instead of asking where they live, what they do for a living, and maybe even discussing their nuclear families, they first discuss what part of Kurdistan they were from, they name the head of their lineage, and list any other prominent relatives. The point of all this is to try to find relatives that they both know, and who they both might be related (Brenneman,67).

Kurdish kinship is a complex web of genealogical relationships. There are several reasons anthropologists can point to for its complexity. First of all, the terminology is not consistent from tribe to trib. Another problem is how extensive kinship can be. A single tribal leader can have 1,000 to 3,000 kin, most of whom he will never meet (Brenneman,67).

Xwin Dari

While the Kurds complex network of kinship can have its advantages, it also can be quite detrimental if there is a “falling-out” (Brenneman,67). A sea of friends can soon become an ocean of enemies that can result in xwin dari or blood feuds. In the United States, blood feuds have been relegated to legions ( like the Hatfields and the McCoys) and organized crime ( like The Sharks and The Jets), but in Kurdistan blood feuds are common in most tribal communities and can even last for generations. In blood feuds, the male relatives of a gravely dishonored, physically harmed, or murdered person are bound by duty to avenge their relative either by seeking revenge against the perpetrator or the perpetrators family (Brenneman,68).

Though common, blood feuds are not encouraged and tribal chiefs try to settle any disputes before they can develop into a major xwin dari. The settlement generally involves blood money or xwin being given to the injured party by the offender. Often, the xwin is a horse and/or the giving of a girl as a bride. More and more though, tribalism among the Kurdish people is decreasing. While more formal governmental law is replacing the traditional tribal law. With this shift, blood feuds are decreasing in severity, duration, and amount (Brenneman,68).

Family

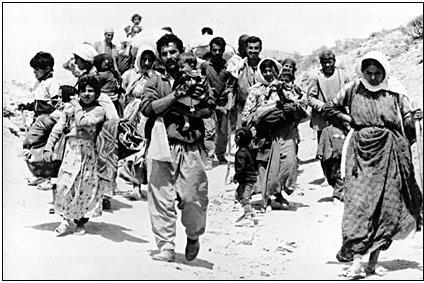

Kurdish families, as in most Middle Eastern societies, tend to be patriarchal, patrilineal, and patrilocal (Brenneman,68). Though, due to political unrest and governmental persecution of the Kurdish people that has lead to a large number of mens’ deaths, it is not abnormal to have an elder female as the head of a family. The head of a family has a very prominent role in his/her family. It is not uncommon for a young Kurd to, even after moving abroad and earning a graduate degree from a Western university, consults their father or grandfather before marrying or even making a major career change (Brenneman,69).

The Kurdish family dynamic may seem extreme compared to the liberties seen in young adults of the United States but Kurdish families are judged by the greater society by the values that they instill in their children (Brenneman,70). It is the suppression of the Kurdish ethnic identity, history, and cultural expression by many overseeing governments throughout history that has led to enculturation becoming vital to the survival the Kurdish culture. Kurdish parents and grandparents teach their children important moral values, like many families throughout the world, but it has also become necessary to impart a sense of Kurdayati to their children as well (Brenneman,71).

Kurdish tradition values having a large family. This is probably because a large family provides more labor in rural areas (www.indybay.org,2009). Like the in the United States, Every child’s birth, boy or girl, is celebrated with joy. Children are expected to be obedient and dutiful to their elders and generally that do not object to the decisions of their parents (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009)

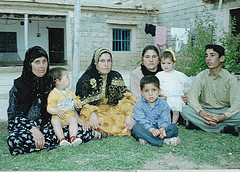

A household is a community in which an extended family may live under the same roof, xani, or break up into smaller sub-units of nuclear families on the family compound. Kurdish extended families not only include parents and their unmarried children but also their married children and their offspring. An extended family may also include the unmarried sisters and brothers of the male head of the family. In a Kurdish household, production, reproduction, distribution, and consumption all take place for the subsistence and advancement of the family as a single unit. Household production is actually the production of all the members of the family compound. The creation of permanent wage-jobs and the modernization of urban families is changing the way traditional households are run (http://family.jrank.org/pages1025,2009).

.

Sex

Due to the diversity of countries in which the Kurds live, there are many differences in the way sex is viewed and discussed. For example, sex is openly discussed among Turkish Kurds but not much among Iraqis (Brenneman,71). Also interesting is the presence of homosexuality and prostitution. According to some anthropological literature “homosexuality may occur among unmarried adolescents if it is discreet (Brenneman,72).” The sex of the individuals engaging in homosexual behavior is not mentioned. However, one can ascertain from further understanding of the Kurdish culture that they must be male since woman’s virginity needs to be preserved till marriage (Brenneman,71). There is also the belief that a man can become sick if he does not have sex regularly and that the lack of sex makes a man less of a man. The latter can also be seen in many western cultures. Interestingly, prostitution, especially in Turkey, where there has been an influx of woman from the former Soviet Union who bring their trade to even small remote villages, has become an outlet. Usually an older relative such as a brother, Uncle, or even farther will introduce a young man to the world’s oldest profession (Brenneman,72). This is also seen in the United States, though not common, some fathers encourage there sons to lose their virginity with a professional.

Marriage

In the Kurdish culture marriages are traditionally arranged marriages in which arrangements may have been completed before the children were born (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009). Even if the marriage is not arranged, the bride and groom do not typically know each other very well. Instead it is the families who do know each other. As mentioned before the individual is judged by their family’s reputation. The parents will assume that if the family is good that the son or daughter will be good. Kurdish marriages are like many other Middle Eastern marriages (Brenneman,72). It is a family event in which two families’ networks come together in a very strong bond (Brenneman,76). A reason that this bond is so strong is that Kurdish tradition state that the eldest brother and his wife and their children are to live with his parents. As a families resources grow, younger brother that marry will go out and build their own houses and move into them, which gradually enlarges the family’s compound (http://family.jrank.org/pages1025,2009). It is this strong kinship and economic tie that can mean a divorce will be catastrophic, not only socially but economically (Brenneman,76).

Marriage is a rite of passage that marks the way into adulthood for both boys and girls. The age at which young people get married varies according to socioeconomic class and the specific needs of the individual families. The marrying age of boys is typically older than girls but this is dependent on an assortment of social and economic strategies of the family (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009). Traditionally, when a girl reaches the age of 10 or 12 and she starts developing, she will be confined to her household by her parents for her protection. She will then usually marry within a few years (Brenneman,81). When there is a labor shortage in a family, the marrying of young girls may be postponed. In urban areas the marrying age is also higher due to the fact that young people are educated and employed in a wage earning job (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009).

Family payment for brides is still Kurdish custom (www.indybay.org,2009). Kurds give the family of the bride a bride-price at the time of the betrothal or in installments until the wedding ceremony. The bride-price is generally paid in cash and gold and may even include gifts to the bride and her family, the expenses of the wedding itself, and/or the construction and preparation of a room for the marrying couple. Now, the amount of the bride-price does vary according to the wealth and social standing of the groom’s family. But, a single bride-price can be as much as one year’s income for an average sized household. There is a discounted bride-price for patrilateral parallel cousin marriages. It is common for the fathers to use the bride-price from their older daughters’ marriages to pay the bride-price for their younger sons’ brides. Trousseau and dowries are also prepared by Kurdish fathers of young women and may include jewelry and livestock for their daughters. Kaleb or sirdan is also presented to the mother of the bride, typically in the form of gold jewelry, for the loss of her daughter (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009).

Some marriages eliminate the use of a bride-price. In a direct exchange marriage or pe-gehurk, the head of one family give a daughter to another family as a wife for their son. In return a wife is given to the first family instead of a bride-price. An example of this practice is a sister exchange. There are even cases of 3-way exchanges. Eloping and ravadin also eliminate the bride-price for most Kurds, but they bring shame to families and ruin the girl’s reputation and she cannot be returned to her family (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009). In some urban marriages there is no bride-price but rather the groom’s family is obliged by contract to pay the bride’s family in the event of a divorce (www.indybay.org,2009).

An important way the Kurds have been able to maintain Kurdayati is by having a strong preference for marrying other Kurds. Keeping bride and groom from within the same village enables the village to hold onto wealth (www.indybay.org,2009). This is not to say that Kurds do not marry outside of their culture. Saddam even gave monetary rewards to Arabs who married Kurds. His motive was to assimilate the Iraqi Kurdish people faster. Saddam had good reasons to believe that a Kurdish-Arab marriage would diminish the Kurdish culture. Generally, when a Kurd marries a non-Kurd, the Kurdish language and culture are sacrificed and their children learn to speak only Arabic or Turkish. Kurds living in the United States have been known to go back to Kurdistan to marry a fellow Kurd, even if it means having to wait years for a visa in order to return to the United States (Brenneman,75).

Marrying a foreigner is not taboo, in fact it is considered better than marrying an Arab. In Turkey, men have access to pornography that lends certain sexuality to Western woman, in addition to them already being appealing for their access to the West and the family prestige they would receive. There have even be incidents of Turkish men getting tourist visas to the West for the specific purpose of finding a bride and getting married (Brenneman,75). More often than not though, Kurds are hesitant of marrying a Westerner because of the West’s casual view of divorce (Brenneman,76).

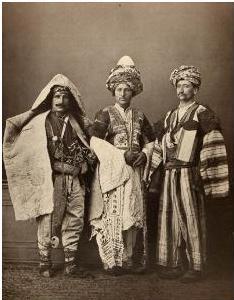

In traditional Kurdish culture, the preferred marriage partner goes beyond just marrying another Kurd. The Kurds practice patrilateral parallel cousin marriages, or what is referred to in Kurdish as akaraba eviligi, in which the father’s brother’s daughter or son is the ideal mate. This is quite common in the Middle East. It is a way for families to keep property in the family and to reinforce patriarchal tribal solidarity (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009). The bride and groom are given a choice; they do not have to marry their cousin, but it is traditionally offered first. Endogamy is not the only normal form of marriage; in fact exogamy is just as common (Brenneman,72). The family almost always oversees the mate choosing process but children are generally given the choice of whoever they want to marry—as long as their choice’s social and economic level is in line with their own. Otherwise the child might not receive their parent approval and have to elope. As mentioned earlier, sometimes a daughter is given in marriage to another tribe as a settlement to an xwin dari. Other times, a daughter is married off for financial reasons, like to get out of debt that the family otherwise would be unable to pay back (Brenneman,73). Another custom common in villages is that Kurds will arrange multiple marriages between families. For example, two sisters marry two brothers. This practice builds a stronger family bond and greater economic benefits (Brenneman,74).

Marriage and courtship are slightly different in the cities. Generally, Children are given greater choices, though arranged marriages still occurs. But for the most part city marriages have more emphases on compatibility. Even with all this freedom, families still are heavily involved and courtships are still short, which gives the couple little time to really get to know each other (Brenneman,74). Traditionally, after marriage a woman will leave her birth household and move to her husband’s village. Typically, she did not have to move away from her lineage territory to move to her husband’s village because most marriages were within the lineages of villages within a short distance of each other. Recently, urban migration and diaspora relations are resulting in more modern marriages where woman even have to cross national borders (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009).

There is also an alternative marrying style that Kurds can choose. Islam allows a man to take up to four wives if he treats all his wives equality (Brenneman,74). Generally, the wives are ranked in statuse by their age (www.indybay.org,2009). This practice is called polygyny. It is not very common, but it is present. One reason for polygyny is economic. The more wives a man has, the more children he can have, which means more potential labor. Another reason for polygyny is if a man’s first wife cannot bear children. This is every Kurdish woman’s nightmare. When this happens there are two options: divorce or a second wife is taken. The laws on polygyny vary from country to country. In Iraq, polygyny is legal but frowned upon. In Turkey it is illegal. If a Kurdish family practices polygyny in Turkey, the second wife might have to be passed off as a daughter or other relative (Brenneman,74-75).

Kurds also practice sororate and levirate marriages. When a woman is widowed she stays with her husband’s family. A levirate marriage will take place if she is widowed when her children are still young. A sororate marriage takes place when a man loses his wife before she is able to bear children or if she dies leaving young children. Usually for this second marriage the bride-price is lowered. These practices guarantee the welfare of the children and makes sure that inheritances will stay in the family (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009).

Courtship does not always fallow the parental rules. As in every culture, many rules are broken. The Kurdish have a practice called ravadin. If a man wants to marry a woman but their families do not approve, he may commit ravadin or a bride-napping. The English translation loses some of the romanticism. Most times the ravadin is consensual on the bride’s side. As mentioned before, reasons for a family’s disapproval can be from class or statues incongruities. A ravadin does not guarantee a happy ending. Many times it can lead to an xwin dari and even excommunication of the couple from the family. It could take years to recover from the implications of the ravadin (Brenneman,72). Sometimes, in urban areas, young girls will threaten to elope, something that will bring shame on the family much like a ravadin, in order to negotiate the marrying of a boy of her choice (http://family.jrank.org/pages1026,2009).

Married life of the Kurds is also unlike that of Americans. Affection is not shown openly between husband and wife but some affection is shared. Most of the social and emotional needs however, are met not by a spouse but by relatives of the same sex. This is a reasonable expectation when marriage is generally for economics and children and not for romance or companionship. Male adultery is not considered serious, but a woman who commits adultery can be killed by her husband or another male relative (Brenneman, 72). Husbands of wives who have committed adultery are subject to reticule and marked as not being able to sexually satisfy his wife (Brenneman, 98).

Things are changing in the Kurdish culture though. The outside world is influencing the traditions of the Kurdish. Though girls still get married relatively young, they are still older on average than young brides 20-30 years ago. Brides are still expected to be virgins though, especially in the villages (Brenneman,71). Akraba evliligi is also waning in popularity as people become more informed of the high risk for birth defects (Brenneman,73). Young people are also being exposed to the idea of romance. It is a popular theme in Turkish/Kurdish music, films, and television. Some young Kurdish couples are even choosing to live together outside of marriage and others are sexually promiscuous (Brenneman,76).

Gender Issues